By Aram Arkun

Mirror-Spectator Staff

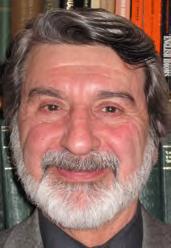

NEW YORK CITY — Dr. Kevork Bardakjian was a recipient of the Ellis Island Medal of Honor on May 7 here. Sponsored by the National Ethnic Coalition of Organizations (NECO), the award recognizes the immigrant experience as well as individual achievement. This year, Bardakjian was one of seven Armenian winners of the award. There is an Armenian on the NECO Board, Irma Der Stepanian, and a number of Armenian- American organizations are part of the NECO coalition, including the Armenian Assembly of America, the Armenian General Benevolent Union, the Armenian National Committee of America, the Diocese of the Armenian Church of America (Eastern) and the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research.

There were various members of ethnic groups singing or dancing at the entrance to Ellis Island hall, including Armenians and a sumptuous dinner was followed later by fireworks. One hundred awardees from many fields of work were recognized in the presence of several hundred people, including family and friends of the awardees. The event finished late, with many returning to their hotels or homes around midnight.

Bardakjian gave his impressions from that weekend: “It was a very dazzling ceremony. It was pomp and circumstance. The army, navy and air force were all represented with bands. Several people made speeches. Jerry Lewis popped in and said a few words. It was very well organized and you truly felt that you were being honored. It made you think back about the path you have traveled in your career.”