By Dorian Jones

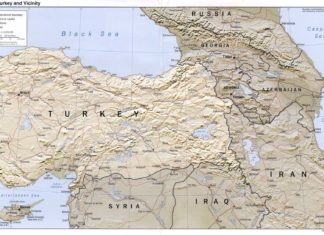

Tens of thousands of Kurds are taking part in an increasingly potent act of civil disobedience that has become a focal point of an increasingly bitter election contest between the governing Justice and Development Party and Kurdish nationalists in Turkey’s restive Kurdish southeast.

In Diyarbakir, the region’s main city, every Friday since March, Muslim worshipers have boycotted prayers at state-controlled mosques to hear sermons in their native Kurdish, conducted in front of the city wall.

“We are Kurds. This is our native language, the language that our parents taught us. Let us speak this language in the courts, in the mosques,” one worshipper said. “Until we are no longer forbidden to speak Kurdish in our mosques, we will do our prayer on the street.”

A crowd of exuberant worshippers applauded the man. Those attending represented a crosssection of society: young, old, rich and poor. In a region where acts of civil disobedience are rarely tolerated, dozens of police, backed by armored vehicles, looked on, but did not intervene.

Kurds make up an estimated 20 percent of Turkey’s 70-million population. Until the late 1980s, the Kurdish language was banned. Under successive governments, restrictions have slowly been eased in education and broadcasting, but Turkish remains the only official language in mosques.