By Sindya N. Bhanoo

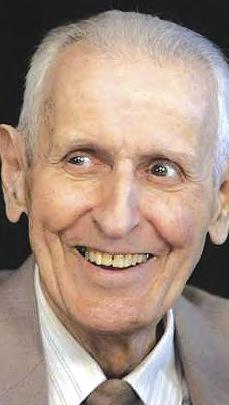

ROYAL OAK, Mich. (Washington Post) — Jack Kevorkian, 83, the zealous, straighttalking pathologist known as “Dr. Death” for his crusade to legalize physician-assisted suicide, died June 3 at a hospital here.

He had been hospitalized since last month with pneumonia and kidney problems, close friend and attorney Mayer Morganroth told the Associated Press.

Kevorkian spent decades campaigning for the legalization of euthanasia. He served eight years in prison and was arrested numerous times for helping more than 130 patients commit suicide from 1990 to 2000, using injections, carbon monoxide and his infamous suicide machine, built from scraps for $30. Those he aided had terminal conditions such as multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and malignant brain tumors.

When asked in a 2010 interview by CNN’s Anderson Cooper about how it felt to take a patient’s life, Kevorkian said, “I didn’t do it to end a life. I did it to end the suffering the patient’s going through. The patient’s obviously suffering — what’s a doctor supposed to do, turn his back?”