By Edmond Y. Azadian

After Kosovo declared its independence in 2008 with the support of the Western countries, the Serbian government brought the case to the International Court of Justice in The Hague, accusing Kosovo of violating international law.

On July 22, the court made its verdict public that Kosovo had not violated any intentional law. The verdict is of an advisory nature and thus not enforceable. The Belgrade government refused to accept the verdict, but it does not have any recourse to reverse it, since the godfathers of that independence have already a 10,000-strong UN force in place “to preserve” peace. Actually, it is to forestall any potential revanchist move from Belgrade or the Serb minority regularly harassed by the Kosovar in their region.

As much as the verdict was symbolic, the reaction from the Serbian president was equally academic, ruling out the use of force to reverse the course inKosovo. Besides, the Belgrade government is very anxious to join the European Union, and with that prospect in mind, has cooperated with theWest and the International Court by handing many former Serb leaders to the court aswar criminals.Of course, trying to commit that murder in the middle of Europe could not go unseen.

The court verdict stirred many reactions from different quarters. Countries which upheld the principle of territorial integrity raised their voices against it, while others, who believed in the principle of self-determination, spoke the opposite.

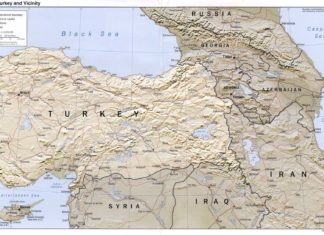

Some countries were caught between the two principles: Turkey recognized Kosovo’s independence, although itself is in a controversial position; Ankara is for self-determination in Northern Cyprus, but against that principle in the case of the Karabagh issue.