By Anna Yukhananov

Special to the Mirror-Spectator

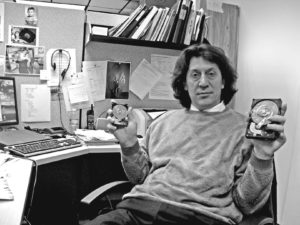

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — Alfred Demirjian, the founder and chief executive of one of Boston’s first data recovery companies, careens through a yellow light before merging across four lanes onto the expressway. He speeds up, then takes both hands off the wheel to adjust the radio tuner.

“When I drive, I think,” Demirjian says. “It calms me down.”

He must be back in the office by 6 p.m. to collect a package from a customer. In the world of data recovery, there are no regular business hours.