By Edmond Y. Azadian

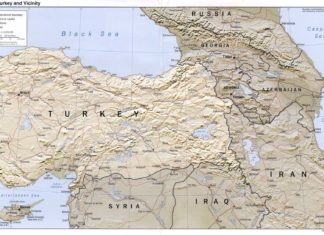

On January 19, 2007, as I was watching CNN News at the editorial offices of Azg daily newspaper in Yervan, a “breaking news” headline was flashed on the screen followed by a shot of Hrant Dink, fallen on the pavement in a pool of blood with his oversized shoes facing the camera. I was overwhelmed by disbelief and I felt that Hrant would rise again and walk in those shoes. That walk was never to be. Instead, his memory and his name walked in the streets of Istanbul, with thousands chanting “We Are Hrant,” “We Are Armenian.”

I had flashbacks of him during our meetings when I used to ask him jokingly: “Hrant, how come you are not in jail?” and his serious answer would be, “Turkey is changing.” Yet Turkey did not change soon enough to save his life.

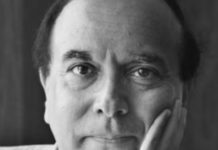

Hrant had become a legend during his lifetime and he turned into an icon after his demise, symbolizing human rights in Turkey and the world over.

Hrant Dink was known for a long time as a human rights advocate. However, in the repressive atmosphere of Turkey, any word about human rights would bring about the label of a leftist, or Communist in order to discredit the person and his ideas. However, in Hrant’s case, those ideas became concrete threats to the Turkish nationalism when he began publishing his bilingual weekly Agos in 1996, with unprecedented circulation figures for an Armenian publication in Istanbul. Through his courageous stand and with the contributions of prominent Turkish writers, Agos catered not only to the young generation of Armenians — who are mostly Turkish speaking — but also a large number of Kurds and Turkish intellectuals.

He was not only persecuted by Turkish nationalists, but also by the Armenian community’s establishment and was envied by his Armenian colleagues, because he was a non-conformist and was brave enough to stand for new ideas. He was walking off the beaten path.