By Michele Wilson

(Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series of features exploring the rich histories and traditions of Bergen’s diverse cultures.)

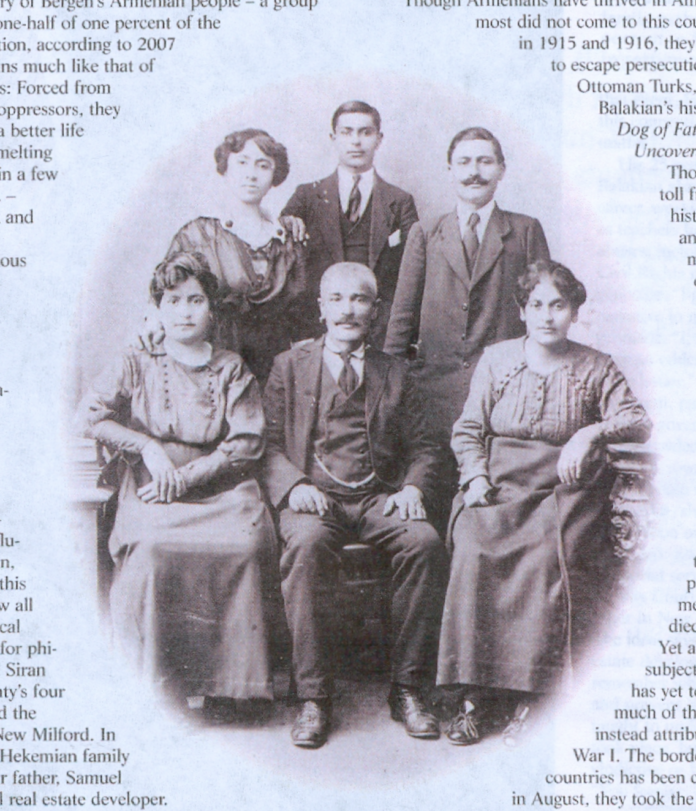

BERGEN, N.J. (201 Magazine) — The unknown story of Bergen’s Armenian people — a group that comprises one-half of one percent of the country’s population, according to 2007 US census data — begins much like that of many immigrant groups: forced from their homes by enemy oppressors, they cross an ocean to find a better life in the giant American melting pot. They set up roots in a few clusters across the US — proximity to New York and silk mills in Paterson making Bergen an obvious choice — and build a community with the church at its center.

Then their story veers. They achieve great success by emphasizing education and community, allowing them to move from Paterson to Fort Lee and Englewood Cliffs, and eventually, to communities even more affluent. As soon as they can, they start giving back; this group’s influence is now all over Bergen: in a medical center pavilion named for philanthropists Sarkis and Siran Gabrellian. In the county’s four Armenian churches and the Hovnanian School in New Milford; in the library donated by Hekemian family members to honor their father, Samuel Hekemian, a successful real estate developer.

The Armenians who populate this corner of northern New Jersey are extremely proud of their accomplishments. “Armenians go back 3,000 years or more,” says Dennis Papazian, former dean, and director of Armenian research at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, who now lives in Woodcliff Lake. “You don’t last that long as a people unless you’ve got something going for you.”

Karen Topjian, born and raised in Bergen, who founded MCM Designs, explains what that something might be: “We are close-knit, family-oriented, education-oriented, community service-oriented,” she says. “Those core values have guided us…Christian faith has also guided us.”