By Taleen Babayan and Alin K. Gregorian

Mirror-Spectator Staff

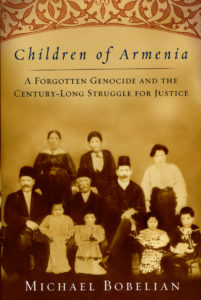

NEW YORK — Author Michael Bobelian’s first book, Children of Armenia: A Forgotten Genocide and the Century-Long Struggle for Justice, which focuses on the aftermath of the Armenian Genocide, was recently published by Simon & Schuster.

Bobelian spoke this week about his book, the thrust of which, he said, is finding out why the world forgot about the Armenian Genocide very soon after the events.

“Most of my book focuses on the aftermath of the Genocide. That is an era no one has written about, neither in historical nor journalistic circles, so it made it very challenging because I had no books to rely upon to act as a guidepost. But it also made it fascinating because no one had written about it. I got to see original material and look at it in a way no one has before. I covered comprehensively the legislative battles, the [Kourken] Yanikian trial and its impact, and the 1965 demonstrations that began the modern Armenian campaign for justice.”