BOSTON – Christopher Young, a retired Crown Court judge from England, gave a talk titled “What Attracted H. F. B. Lynch to Armenia? Origins and Influences” on October 1 at Boston University, organized by the Charles K. and Elisabeth M. Kenosian Chair in Modern Armenian History and Literature at the university.

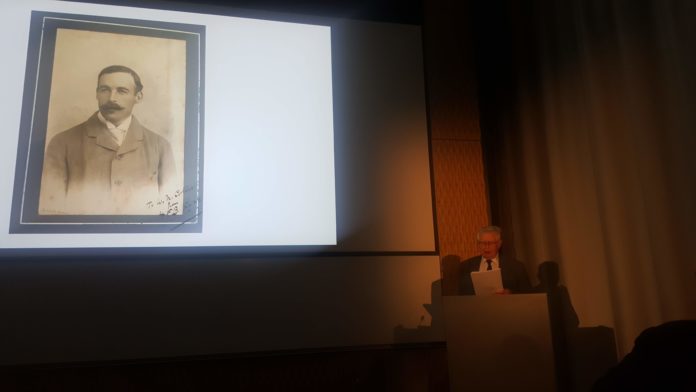

Henry Finnis Blosse Lynch (1862-1913), informally known as Harry, is most famous for his comprehensive two-volume work, Armenia: Travels and Studies, published in 1901 with plentiful illustrations, which covers Armenian geography, history, architecture, culture and politics in detail. Young focused in his talk, illustrated with slides, on Lynch’s Armenian family connection, his commercial, political and military interests, and his interactions with various contemporary English political figures. He was introduced to the audience by Prof. Simon Payaslian, holder of the Kenosian Chair.

The story began in the 1790s, when Lynch’s maternal grandfather, 20-year-old ensign Robert Taylor, was sent to Bushire to learn Persian as part of the British East India Company (EIC) army, and eloped with Rosa, the 12-year-old daughter of Hovhannes Moscow, an Armenian merchant of Shiraz. Taylor, who eventually became British consul and resident at Bagdad, had four children with Rosa. One of these daughters, Caroline, married Lt. Henry Blosse Lynch, of the EIC navy.

The latter saw potential for commerce and navigation on the Tigris and invited two of his brothers to join him from the family home in Ireland. Thomas, a classical scholar of Trinity College in Dublin, ended up marrying Harriet, Caroline’s sister, who became the mother of H. F. B. Lynch. A second brother, Stephen, married a daughter of another Armenian merchant. The three brothers founded the Lynch Brothers, which later became the Euphrates and Tigris Steam Navigation Company.

Young, basing himself on published and unpublished works by Lynch family members as well as documents such as wills and census returns, concludes that the Lynches were “wealthy, cultured, well connected and ambitious.” Thomas became British consul-general for Persia. Both he and Stephen brought their families to London, while maintaining mansions and land in Basra and Baghdad. Rosa, who had become a widow and blind, lived in London with Thomas and Harriet.

H. F. B. Lynch was born there in 1862, and his Armenian grandmother died 15 years later. He also grew up near his uncle Stephen’s Armenian wife Hosanna and interacted with his mother’s brother John George Taylor, who had become British consul at Erzerum and traveled with his Armenian dragoman.