By Aram Arkun

Mirror-Spectator Staff

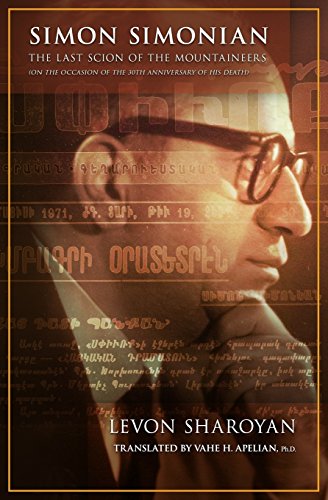

Simon Simonian was a prolific author, editor, publisher and teacher who played an influential role in Armenian diasporan life. An initial attempt at presenting his legacy in English has been made by Levon Sharoyan of Aleppo, in Simon Simonian: The Last Scion of the Mountaineers (On the Occasion of the 30th Anniversary of His Death). First published in serialized form in the Armenian-language periodicals Kantzasar, Aztag and Harach, and then as a volume in Armenia, this short work was translated into English by Dr. Vahe H. Apelian and published in 2017 by Hratch Kalsahakian with the sponsorship of the Simon Simonian Fund.

This volume is not a scholarly monograph but a very personal approach to Simonian’s works. Sharoyan’s grandfather “Shoemender Levon” is one of the Sasun Armenians living in Aleppo about whom Simonian wrote in his stories, and Sharoyan grew up reading Simonian’s various writings. Several Simonian family members edited and proofread the translation.

Simonian was born in Aintab in 1914. His father was from the Germav village of Sasun. His family fled to Aleppo in 1921. Simonian was accepted to the newly opened Seminary of the Catholicate of Cilicia in Aleppo and graduated as part of its first class in 1935 together with the future Archbishop Terenig Poladian and Catholicos Zareh Payaslian. He then returned to Aleppo to be a teacher of Armenian language and history at the National Haigazian School till 1938, and again from 1941 to 1946. He taught from 1938 to 1941 at the Gulbenkian Armenian School.

One of Simonian’s most important legacies is the publication work of the Sevan publishing house, which he first started in 1945 in Aleppo and restarted in 1954 in Beirut. He published and edited two issues of a literary periodical called Sevan in 1946, sponsored by the Armenian Teachers’ Association of Aleppo, which printed the works of many prominent writers, including Catholicos Karekin I Hovsepiants, Nigol Aghpalian, Vahan Tekeyan and Hagop Oshagan.